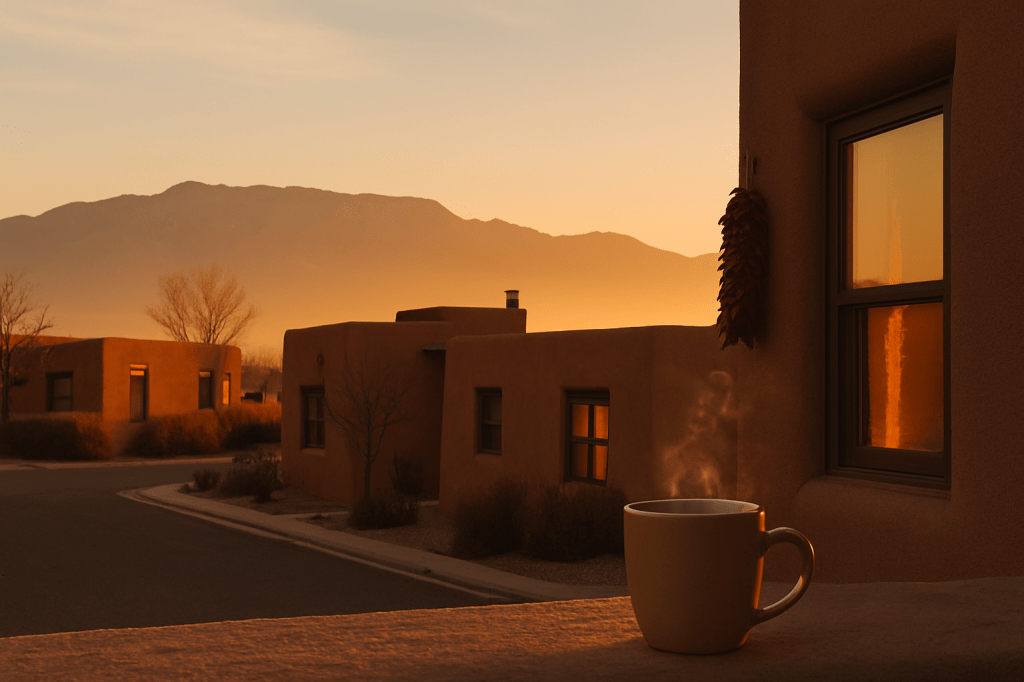

I bought a vehicle that can go anywhere—mountains, mesas, the forgotten roads that stretch like veins across the desert. Yet somehow, I’ve gone nowhere. There’s an invisible hand that holds me in place, the same quiet force that makes stepping into a restaurant alone feel like walking into a storm. I need purpose, or company, or both, to push past it.

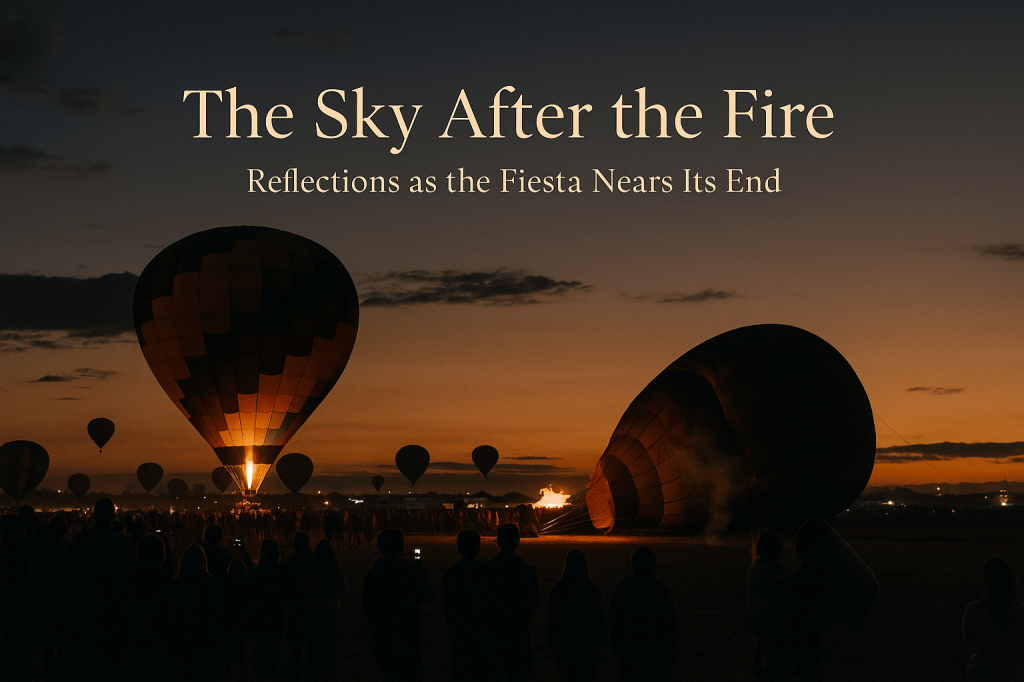

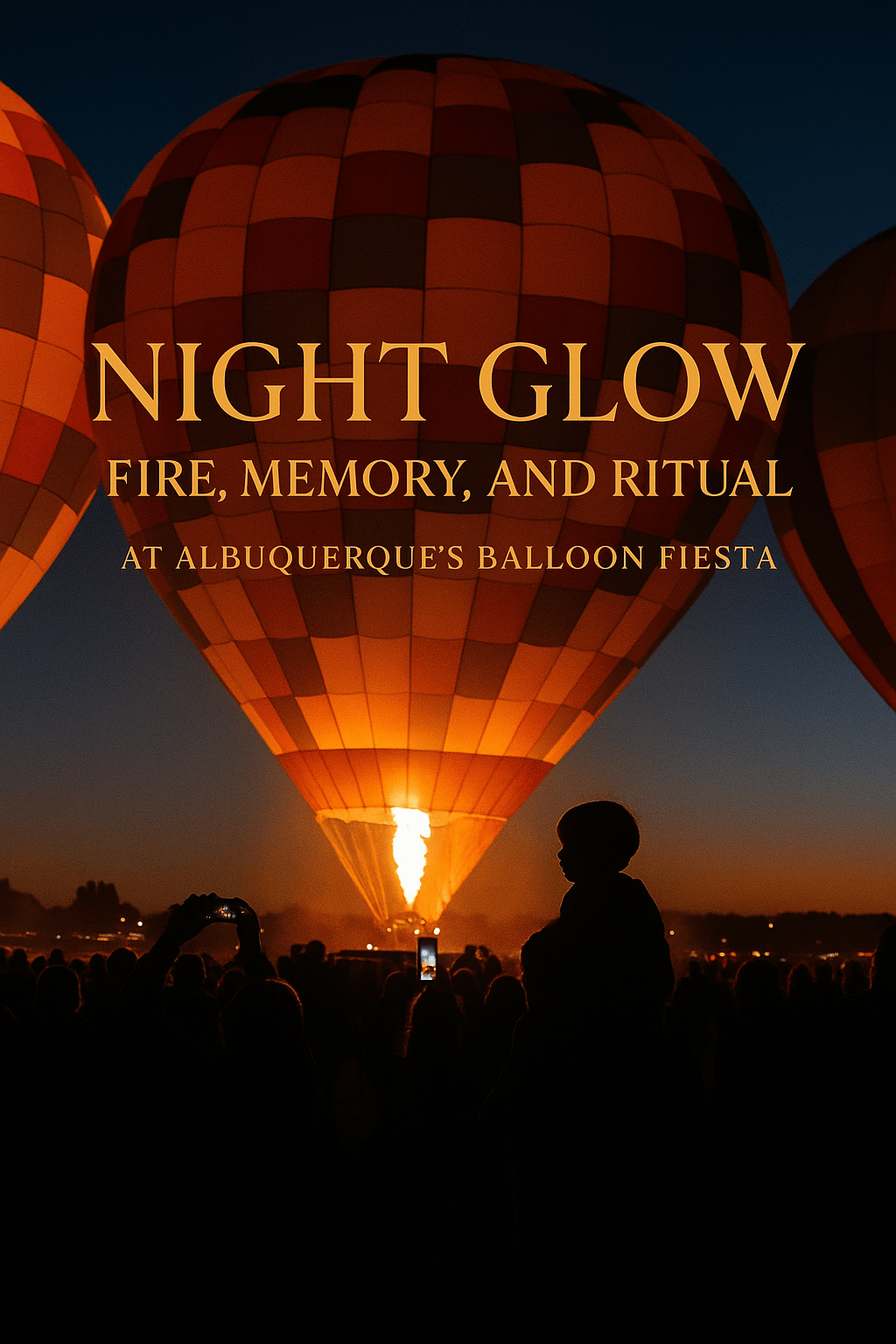

Lately, though, the sky has been whispering louder than my fear. During the Balloon Fiesta, I watched people from every corner of the world stand in awe of the same morning light I’ve taken for granted. Strangers were out there feeling the beauty of this place—my place—while I stood behind my walls, waiting for permission to belong. That realization loosened the hand’s grip just enough for me to move.

So I began small.

Tiguex Park

Tiguex Park isn’t large or loud. It’s one of those places that feels like an exhale—the kind of open green that reminds you the desert can still be gentle. Cottonwoods border its edges, their leaves whispering stories to anyone who’ll listen. The grass carries the echo of a thousand family picnics, soccer games, and lazy afternoons.

I sat on a bench and listened. The wind carried the faint clang of church bells from San Felipe de Neri. A child laughed somewhere behind me; a dog barked once and then twice. The air smelled faintly of dust and Pinon Coffee from stores nearby. I could almost feel the heartbeat of Albuquerque pulsing under the soil—slow, steady, stubborn.

For a few minutes, I wasn’t thinking about where I should be. I was simply here. And that was enough.

Old Town

When I left the park, I drifted toward Old Town, a place I wasn’t even sure I’d ever been. The streets were narrower than I expected, like they were designed to make people slow down and see. My vehicle felt too big for this kind of space, a metaphor I didn’t miss—how often have I felt too big, too loud, too something for the places I wanted to fit into?

I found parking near a cluster of adobe buildings washed in warm earth tones and trimmed in turquoise. Every corner seemed alive with color: handwoven blankets, clay pottery, silver jewelry glinting in the sun. But the crowds pressed close, a river of bodies and voices that threatened to sweep me away. Anxiety whispered, You don’t belong here, and I believed it for a moment.

Still, I stayed long enough to see what I needed to see. The history in the walls. The persistence of beauty. The courage of people who choose to create, to sell, to share, even when the world is watching. Eventually, the noise became too much, and my anxiety reminded me it was time to go. But as I left, I felt something else—I had gone.

Sometimes that’s the victory: motion.

Chile Addict

Leaving Old Town, I wasn’t ready for home yet. I wanted something that spoke to the culture I had only brushed against. A museum? A gallery? Maybe food? I found all three at Chile Addict on Eubank.

If passion had a smell, it would be chile. Inside, every inch of space was filled—ristras hanging from the ceiling like red jewelry, shelves lined with sauces from every corner of New Mexico, even dish towels embroidered with peppers in every shade of fire. I bought a bottle of Albuquerque Hot Sauce, labeled “Extra Hot.” I didn’t realize “extra” meant something different here—this was heat meant for native tongues, not transplants like me. But I loved that. It was honest. It burned like truth.

There was something sacred in that store: the way it celebrated an ingredient that’s more than food—it’s memory, identity, inheritance. It reminded me that culture isn’t confined to museums or galleries. Sometimes it’s bottled, hanging, or simmering quietly in someone’s kitchen.

What Comes Next

Driving home, I thought about how long I’ve let that invisible hand dictate my movements. How many experiences have I let anxiety edit out before they began? This small journey—Tiguex Park, Old Town, Chile Addict—felt like a rebellion against that stillness.

Maybe I should do this every week? Not for content or performance, but as a ritual of re-entry into life. To see my city not as a backdrop but as a living text—one I’ve been too afraid to read.

Exploration doesn’t always begin on the open road. Sometimes it starts at the park down the street, or in the narrow lanes of a place you’ve always avoided. Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is just go.

Maybe that’s what growth really looks like—not grand adventures, but small acts of motion. What do you think… Should I keep going?

Kyle J. Hayes

kylehayesblog.com

Please like, comment, and share