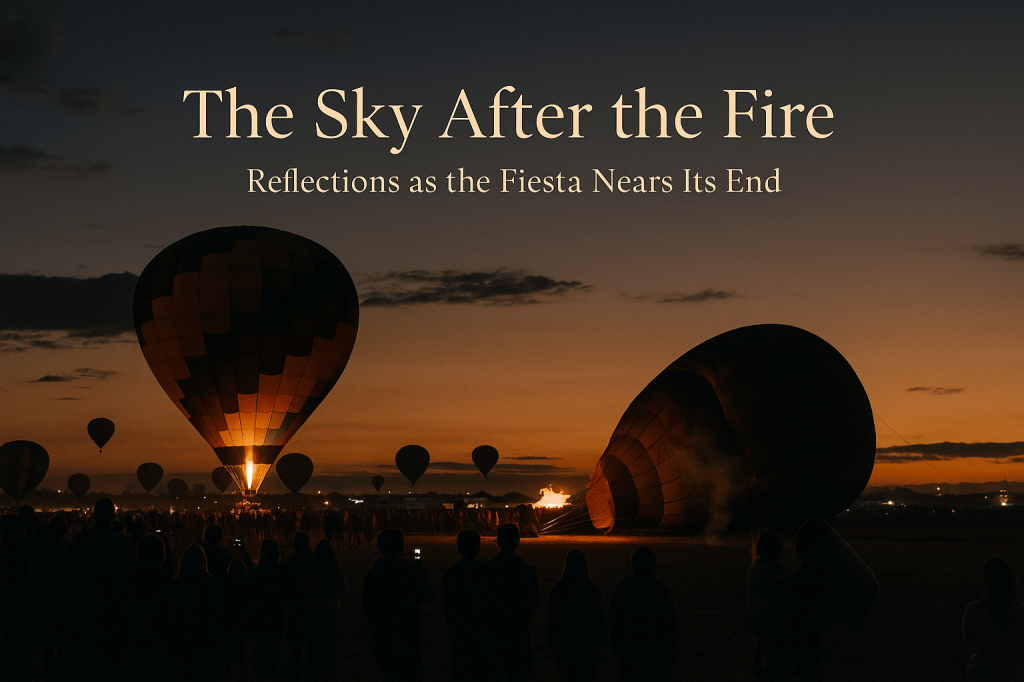

Salt, Ink & Soul — Field Journal Series, Part II

We’ve all heard the phrase, “I’m not as young as I used to be.”

But for me, it’s never really been about age — it’s about gravity. The pull of places, the way life settles you down unless you fight to stay awake inside it. Some people live where they were born, their stories looping through familiar streets and steady skies. I’ve always lived apart — even when I was close, I was at the edge.

People call it a wandering spirit.

I prefer searching spirit. Wandering implies lostness. Searching carries intent — a hunger for something not yet found but deeply felt.

The Pull

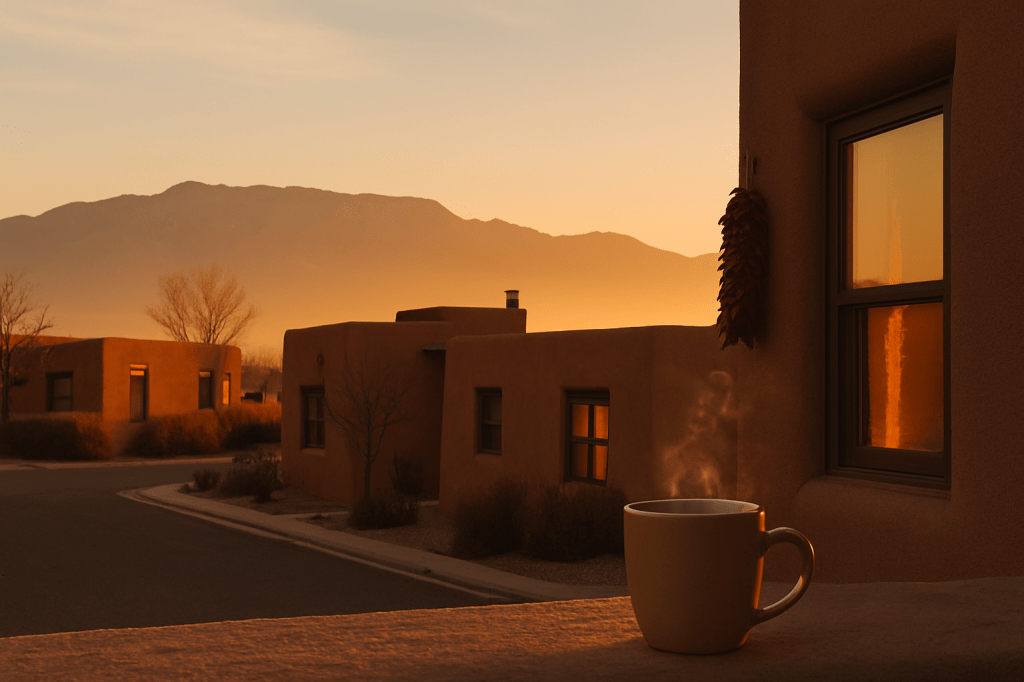

When I first moved to Albuquerque, the desert had its own kind of whisper. The space between things felt wider here — room for thoughts to stretch, for silence to mean something. I learned about Earthship homes — houses built from recycled materials, designed to sustain themselves off-grid and to live with the land rather than against it.

It wasn’t just their design that intrigued me — it was their defiance. They refused permission. They were proof that you could live differently and still live beautifully.

So I made the trip north.

The Earthships

The drive into Taos feels like crossing a threshold — sagebrush to sand, sky expanding until it seems to hum. Then, at the edge of nowhere, the Earthships appear like a dream half-finished — domed roofs, bottle walls shimmering in sunlight, glass catching sky.

I took the tour slowly. Inside, the air felt calm, held. The walls glowed faintly green where glass bottles caught the light. Planters of herbs ran along windows, drinking sunlight and water collected from the rain. It was quiet — not empty, just balanced.

The guide spoke about sustainability, but I was hearing something else — a kind of philosophy of living: build with what’s been discarded, make beauty out of survival. It reminded me that creation isn’t always new; sometimes it’s just rearranged endurance.

The Staircase

From Taos, I drove south to Santa Fe, to the Loretto Chapel. I’d heard the story — the mysterious carpenter, the spiral staircase with no visible supports, built after the nuns prayed for a solution. Seeing it in person was something else.

The staircase curves upward like a question that answers itself — no nails, no center post, just precision and faith. I stood beneath it, tracing the grain of the wood with my eyes, thinking about the people who build because they have to believe it will stand.

The Gorge

Then there was the Rio Grande Gorge — where the land simply falls away.

I parked, stepped out, and felt the wind announce itself. Heights and I have never been friends. I walked to the railing anyway.

Below, the river glinted like a silver thread stitching through time. When a semi-truck passed, the bridge shuddered beneath my feet, and I gripped the rail tighter than I’d admit. But I stayed long enough to feel it — that strange marriage of fear and awe.

That’s what this road was always about. Not conquering fear — just walking out far enough to meet it honestly.

On the drive home, I realized I wasn’t chasing wonder anymore. I was studying it — seeing what remains when the awe fades and only understanding is left.

Maybe the Earthship homes, the staircase, and the gorge were all saying the same thing:

Build something that endures.

Trust what you can’t see holding you.

Look down, but don’t stay afraid.

The road home was quieter. The car hummed its low prayer, tires counting miles of reflection. I thought about all I’d seen, and how every place had its lesson written in silence.

Maybe I’m still searching, but it’s a better kind of searching now. Not for arrival — but for alignment. For the places and people that hold when the ground trembles.

The road doesn’t always offer answers.

Kyle J. Hayes

kylehayesblog.com

Please like, comment, and share