Salt, Ink & Soul — Albuquerque Notes

It’s not silence I’m afraid of.

It’s what it asks me to notice.

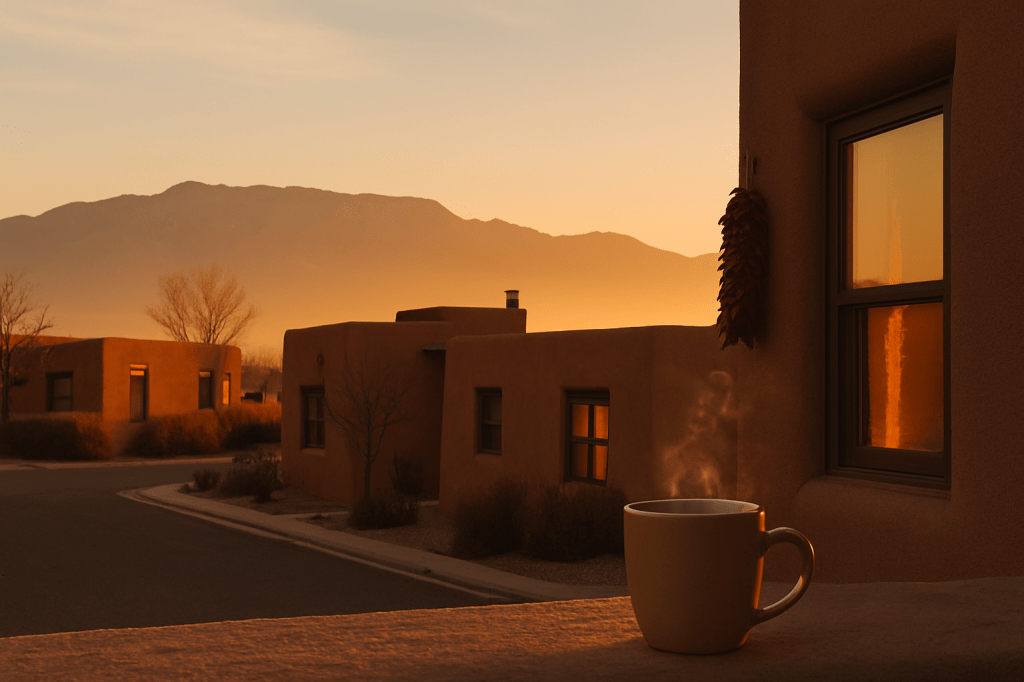

After the city winds down and the last porch light clicks off, a different gravity settles over Albuquerque. The air thins and sharpens. The clock doesn’t tick so much as announce—each second a footstep down an empty hall. Even the refrigerator hum sounds like a confession. Outside, the street goes soft: figures moving like ghosts, wind pushing fine dust into corners as if to whisper, look closer.

In the kitchen at night, I stand there, unsure. Wanting to make something, not knowing if I’m even hungry. Under one dim bulb, a small pool of gold forms on the counter. Tile throws the light back in fragments—little squares of moon you can touch. The sink holds its breath. Somewhere above the cabinets, the house settles into itself, wood remembering the day it was a tree. The room is stocked—spices, onions, bones for broth—but hunger doesn’t arrive on command. The emptiness isn’t in the pantry. It lives somewhere between the throat and the hands.

They say a writer’s greatest enemy is the blank page. They’re not wrong, but that’s not all. Emptiness has cousins: a cook’s dim kitchen when the body isn’t hungry; a road at midnight when the destination is gone and home hasn’t yet declared itself. The quiet asks for something you can’t measure—faith in a spark you cannot see.

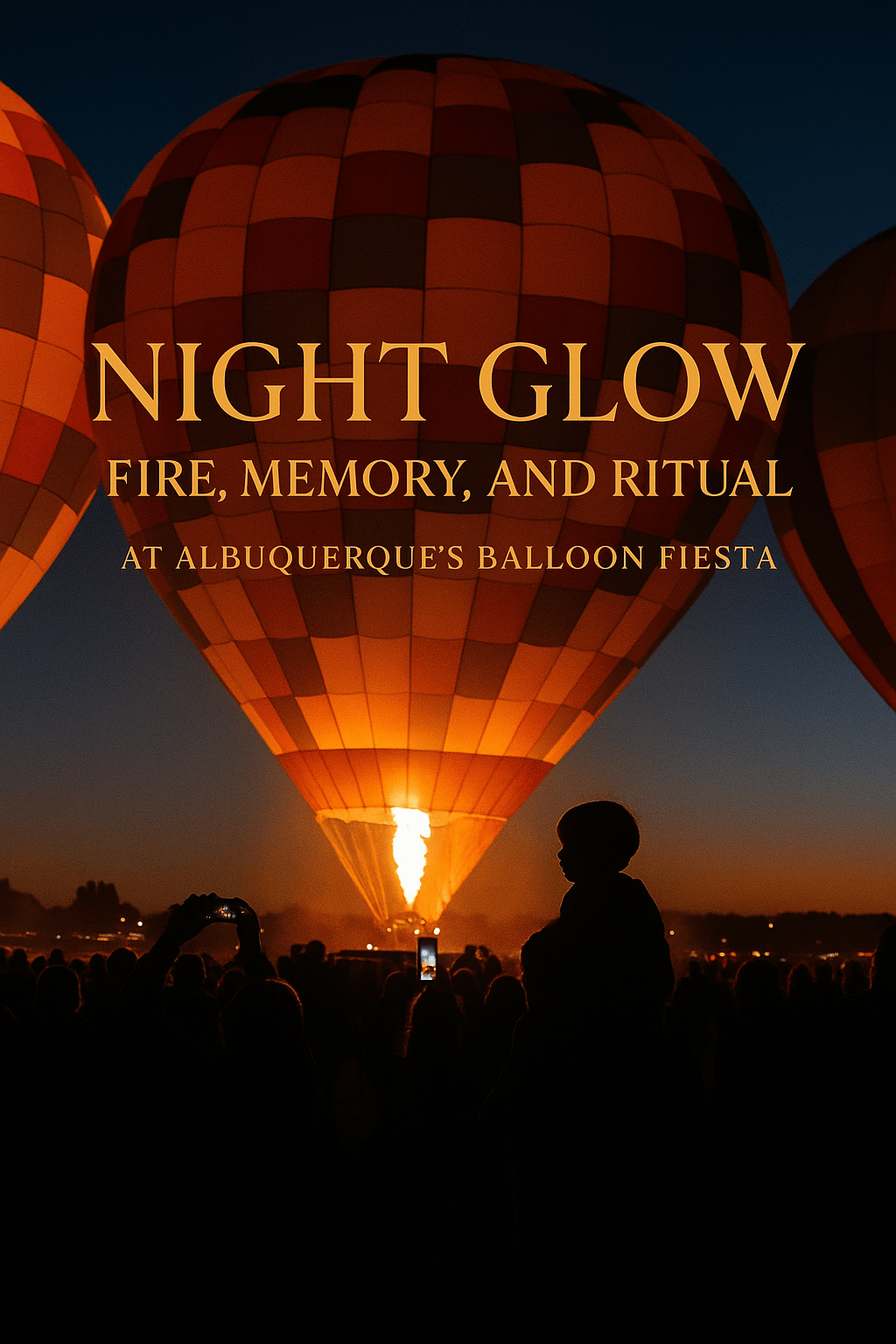

What does it mean to keep creating when the world around you—and inside you—goes still? What do you do when the excitements of special events are gone?

There’s a restlessness inside the calm, like ducks on a pond—serene on the surface, paddling like hell beneath. After the community’s noise, the quiet feels heavier than the rest. It carries expectation without applause, work without witnesses. You can hold peace and pressure at once: the relief of not performing, the terror that maybe the next sentence, the next meal, won’t arrive.

So I walk the rooms, listen to the house breathe, look out at adobe walls silvered by the moon, at porch lights fluttering like low-altitude stars. In this desert city, quiet isn’t absence—it’s landscape. Wind hums in the eaves. A lone car slips past, tires whispering secrets to the asphalt. Somewhere, behind a thin wall, soft laughter breaks and fades—the way a match surrenders after doing its job.

If I cook, I begin with what listens back: onion, oil, salt, low flame. I don’t chase a masterpiece; I court a whisper. Heat slowly, until the room remembers its purpose. If I write, I let the hands move before the story arrives—detail by detail: the scrape of chair legs, the nick on the cutting board shaped like a small country, the clock insisting it is the only drummer left. I ask the night to tell me what it knows that daylight talks over.

Quiet becomes a compass if you let it. It points not north but inward. It wants fewer clever sentences and more honest ones. It returns me to the first question: Who taught you to make something from almost nothing? Who fed you when there wasn’t much to eat? What did their hands look like under this same small bulb?

I used to treat stillness like a problem to solve. I believed I should always be doing something—don’t waste time. Now I try to honor it as part of the work. The pause isn’t an intermission between lives; it’s the dark soil where the next season’s roots grow. It’s where endurance gathers; where healing grows legs.

So I keep the rituals small and faithful. I leave a clean spoon on the counter. I set a glass of water by the notebook. I promise myself ten minutes of heat—words or stove, I don’t care which—then I let the ember decide. Some nights it becomes soup for nobody but me. Some nights it becomes a paragraph that holds after morning. The work is quiet, and it is enough.

Outside, the Sandias keep their shape against deeper blue—mountain patience refusing to be hurried. Inside, the kitchen bulb halos the room like a blessing I didn’t think I’d earned. The page accepts a first line. The pan agrees with the first hiss. The world does not erupt in applause. It doesn’t need to.

The fire worth trusting now is the low one—the barely visible ring that keeps the pot honest; the internal pilot light that refuses extinction. Creation isn’t the thunder of a finale; it’s the stubborn heat that stays when the audience goes home.

The quiet isn’t asking me to fill it—only to listen long enough to remember why I speak.

Kyle J. Hayes

kylehayesblog.com

Please like, comment, and share